About Heliotroph

Heliotroph is a project dedicated to the teaching and promotion of Platonic Philosophical Religion. We believe that the wisdom of the ancients holds valuable insight into the nature of the world and the human soul, and that the application of that wisdom to the modern world is our best hope of recovering fulfilling and sustainable ways of living.

Our Worldview, Logic, and Practice

Platonic philosophical religion, which is a term I am using simply to denote the practice of Platonic and “Neoplatonic” philosophy in its correct context as a spiritual system, is a perennial, mystic, religious tradition with similarities to those of Egypt, India, and many others. This tradition was at times in dialogue with them, as well as perhaps sharing a primordial provenance with them. The tradition derives its label from Plato because the philosophers of the Athenian academy and their successors, such as Plotinus and Proclus, were the ones who provided written elucidation and preservation of the rational, reproducible logic of these truths for the peoples of Europe and the Near East whose intellectual traditions derive from the Hellenes.

While modern people might think of philosophy as a web of abstractions or an attempt to impose categories, order, and logic onto a chaotic world, the Platonist definition of Philosophy is very different. It views Reality as inherently orderly and logical, and philosophy as the process of encountering and adapting oneself to that order. Central to Reality is a simple, subtle, ineffable principle of unity which precedes all things, all beings, and even all nothingness and non-being. Experience and Logical inquiry reveal that a person lives best when he or she is most united, most at-one with the inner self, and thus most at-one with reality. The process of living Philosophy is the process of discerning what that oneness looks like in your life, and then determining and exercising the thoughts, words, and acts which best align with it.

This pursuit is inherently religious. The divorce of philosophy from theology that has occurred in modern times is an arbitrary result of cultural prejudices. All of the philosophers to whom we are indebted for this system practiced the pagan religious traditions of their native cultures, and were quite knowledgeable and enthusiastic about them. A huge part of the purpose of this site is to present an argument that philosophical inquiry and practice is incomplete without some understanding of and appreciation for the ritual and mythological aspects of the cultures that contributed to the Platonic tradition.

The various Gods conceived of by these cultures are in fact integral to several different layers of this practice. They precede, produce, and organize the world – it is made of them and from them. They reach from the very bottom of manifestation all the way into the un-manifested eternity that it emerges from and returns to. They are therefore relevant not just to our loftiest attempts to understand and explore reality, but also to the most basic and mundane aspects of daily life.

It was through intimate, iterative, generational experiences with them that our ancestors devised, received, and refined the mundane practices and symbolic associations of religion and myth. It is these portions of our practice that are currently in the most disrepair, thanks both to earlier Abrahamic suppression and to secular materialism’s ongoing marginalization of the ensouled, spiritual worldview which is natural and proper to human beings. Fortunately, though much work remains to be done, the basics of practice are known and are easily reproducible in our own lives. These practices serve many purposes, with motivations and results as diverse as the wide array of different rites; Naming ceremonies for newborn children, marriage vows, funeral protocols, adolescent rites of passage, prayers for success in work or conflict, prayers for really anything that a person of any faith could want to pray for, simple meditations and exercises, and finally – perhaps the linchpin of the whole system – household ritual devotion, placing the individual and the family into a cycle of generosity with the Gods and spirits of domestic life.

Through all of these different rites there are a few common threads: We turn our gaze upwards in times of transformation or transition. When faced with the confusion and uncertainty of worldly life, we look towards sources, causes, and powers, rather than just their effects. In doing so, we remind ourselves of what is enduring and unchanging and most perfect, which allows us to situate ourselves in the senses of gratitude, awe, and unity which pull us towards our own perfection.

These practices also serve many functions on the merely psychological or material levels, though these are not necessarily their purpose or justification. They stabilize our emotional lives, strengthen our bonds to other people and our environments, and direct our focus towards healthy, constructive things. The Gods reach from the highest to the lowest and invest absolutely everything, providing ideals to strive for in every facet of life. They are just as present in gyms, kitchens, and city streets as they are in their altars, and part of the point of seeking them in temples and in ritual is to accustom ourselves to their presence so that we grow to sense them just as vividly in the mundane as we do in sacred spaces.

How Does One Practice?

Practice can be as elaborate or as simple as your means, goals, and level of understanding permits or demands. Here, we will just treat on what we could consider the bare minimum, which is largely about a certain outlook and system of values that one should strive to embody and some of the very basic rituals conducive to that.

First and foremost is simply prayer, which is much the same for us as for any other tradition. The standard procedure is as follows:

1: Turn your palms upward and recite the name of the God you wish to address, then any of their epithets or roles you wish to focus on, possibly including a reference to a mythic episode of theirs if you are performing a long prayer.

2: Offer them praise and/or gratitude and make your request, though requests are not necessary and simple praise and thanks are very helpful and rewarding on their own.

3: End with more gratitude or with the promise of an offering in the future.

Taken together, a short prayer may look like this: “Lord Hermes, may you guide my words.”

A longer prayer may look like this: “Lord Hermes, slayer of Argus, friend of man, I thank you for your gift of keen thought. May you protect me from ignorance and misunderstanding, and if it pleases you then may you accept my promise of an offering of wine.”

Prayer can be done silently or without outstretched hands if in public or lacking privacy, but it is good to take whatever chances you get to pray out loud. Doing so is very healthy for the mind-voice connection, which is vital to our self-expression and our relationships.

The next practice is the maintenance of a household or personal altar and the use of it for ritual offering. It is acceptable to forego this if you are in a family or roommate situation that would prevent it, but it’s actually quite simple and easy. All that is required is a small flat surface, a candle, and a small bowl or cup. You may find it enjoyable or helpful to ornament the space however you like, especially with icons or symbols of the gods, but all that is strictly necessary is keeping it clean. An altar is important because it creates a physical landmark that serves to call our attention to the divine. It helps to ground our minds in the present moment and anchors us to reality, which is a powerful weapon against stress and listlessness. Keeping an altar accustoms us to setting aside dedicated time and space for divine matters while also reinforcing that doing so can, and should, be part of everyday life and not just restricted to holidays or public services.

The process of offering is also simple:

1: Wash your hands and face and sprinkle the altar with water. If you desire, you can use “khernips,” water which is consecrated by adding salt and dropping burnt plant matter into it.

2: Once the area has been purified, light the candle. To open the altar you may invoke a gateway deity, such as Vesta/Hestia, Odin, Heimdall, or Agni. This deity should receive the first offering, as well as the last one when you end the ritual. If you are only offering one thing, such as a single food item or stick of incense, it is also perfectly fine to simple say something to the effect of “may you accept your due portion of today’s offering.” The most common offerings are libations of water, milk, or alcohol, done simply by pouring the offering into a small vessel on your altar.

3: Next, simply pray as was outlined before, selecting whatever deities are appropriate to the occasion or your issue or situation. The only alteration to the prayer structure is to either make your libations before or after the prayer and to address the offering with words such as “May you accept this gift” or “May you take your due portion of the offered (food/incense/object).”

4: Finally, end the ceremony by thanking and offering to the gateway deity again (if you chose to address one) and then put out the candle.

The third basic practice we will outline here is fairly broad and is more about adopting a way of thinking and acting that is conducive to growth and learning. You should get used to seeking out new information and trying to learn something new every day or at least every week. You should also begin to get acquainted with your own internal landscape, with the entrenched pathways of action and reaction that your thought patterns and habits have carved for you over the years. To become intimate with your body, both its physical and subtle forms, is a vital part of learning to exercise sovereignty over it.

Towards that end, we also consider physical exercise and the vigilant tending of one’s health through habit and diet to be cornerstones of a complete religious practice. While our primary sources on directly spiritual matters tend to neglect health and physical culture, this is simply due to the fact that in the ancient world nature was always close at hand and even human settlements were rich in gymnasia and bath complexes, and therefore basic health could often be taken for granted compared to the very stilted and industrial environment of our day – even so, gods related to health and healing, such as Asclepius and Apollo, were always among the most revered and sought after in daily life.

Almost none of our precursors would deny that a healthy body is vital to philosophic and religious practice, because the strength and clarity of the body’s functions directly influences our minds and our ability to exert attention and engage in inquiry and dialogue. This basic principle is made obvious in everyday life when, for example, one has to go to work on very little sleep. Regardless of what extreme ascetics might get up to, for the average person pain, exhaustion, and sickness tend to distract from the divine rather than drawing one’s attention towards it.

Finally, it is our position that all endeavors in life can be greatly aided by the adoption of an attitude of devotion, trust, and gratitude towards a personal (i.e. not abstract or mechanistic) God/Goddess or Gods. To learn to love the divine as we love our own family or friends is its own reward, but it also creates an emotional environment in our hearts that is best prepared to deal with hardship, to embrace transformation, to trample the hang-ups that keep us isolated from others and from our inner selves, and to recognize when the divine is revealing the best course of action. We support the Hindu conception of “Bhakti,” and reject the beliefs held by certain neopagans that the Gods are morally gray or neutral, merely symbolic of natural phenomena, or are somehow bound and limited by circumstances, like the prevalence of human worship of them, as an egregore might be. We hold the Gods to be total, all-pervading, all-creating beings whose realities we are privileged to participate in and, with practice, unite ourselves wholly with.

Still Feel Unprepared?

One of the most common hurdles for new practitioners is a lack of information on which Gods to worship and how. Part of the reason for this is that many popular sources about the deities currently use a historic or anthropological context instead of a devotional one.

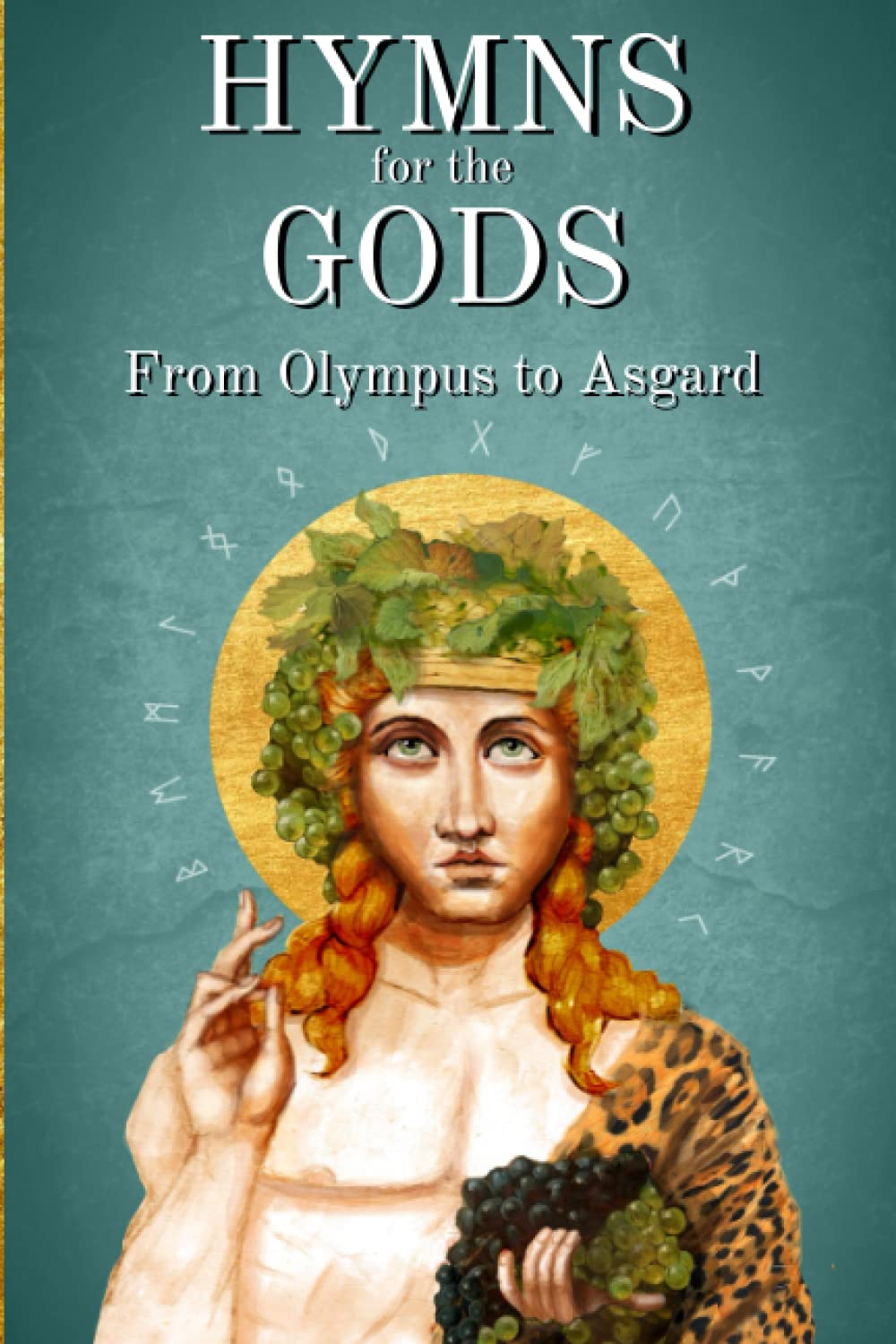

Hymns for the Gods is my small contribution to rectifying that. It is a collection of over 100 prayers to 33 of the most commonly revered Gods of the Hellenic and Norse/Germanic pantheons, including a detailed introduction to each deity that gives the reader valuable information on that God’s role, what matters we should approach them for, and what we owe them gratitude for.

Future editions are planned that will broaden the scope of the work to include Kemetic, Celtic, and other pantheons, and as this website matures I will be adding free resources about the various Gods. But until then, Hymns for the Gods should prove helpful to any beginner, even ones interested in other pantheons, since deepening one’s knowledge of similar gods across cultural boundaries provides valuable insight into the deeper truths embodied by them.